-

CANBERRA: India-Australia partnership aims to bridge skill gap for future employment - April 15, 2024

-

HOUSTON: Mumbai boys in the final rounds of FIRST World Robotics competition to be held in Houston - April 14, 2024

-

MADRAS: IIT Madras NPTEL translates thousands of technical courses into several regional languages - April 10, 2024

-

MUMBAI: Shahid Kapoor opens up about the challenges faced by character actors in Bollywood - April 8, 2024

-

NEW DELHI: World Health Day 2024: Date, Theme, History, Significance and Interesting Facts - April 6, 2024

-

LONDON: Indian-Origin Teen In UK Gets “Life-Changing” Cancer Treatment - April 3, 2024

-

BENGALURU: Indian scientists unravel genetic secrets behind lumpy skin disease outbreak - March 30, 2024

-

NEW DELHI: Youngsters’ Increasing Stress Levels, Early Onset of Diseases an Alarming Health Trend: Apollo Hospitals Chief - March 28, 2024

-

MARYLAND: All About Pavan Davuluri, New Head Of Microsoft Windows - March 27, 2024

-

MUMBAI: Pyaar Kiya To Darna Kya turns 26: Kajol says THIS was the symbol of an innocent girl back then - March 27, 2024

WALES: The student who became a Welsh bard at 19

WALES: An Indian student won acclaim in Wales as a bard and became

the first woman to get a law degree from University College London. And

although racial prejudice brought a heartbreaking end to a three-year

relationship she never went home, writes Andrew Whitehead.

Dorothy Bonarjee was Indian by

birth, English by upbringing, French by marriage – and Welsh at heart.

To put it another way, she was the

perpetual outsider, sometimes by chance, and at other times by choice. Even the

moment of her greatest achievement in 1914 – winning one of Wales’s most

prestigious cultural prizes while still a teenager – is notable above all

because she was so obviously not Welsh.

In India, Dorothy Bonarjee and her

family stood apart, by class, culture and religion. They were upper-caste

Bengali brahmins, but Dorothy spent her childhood living a simple life on the

family estate hundreds of miles away from Bengal in Rampur, near India’s border

with Nepal. They were also Christians – her grandfather served as a Scottish

pastor in Calcutta (now Kolkata) after being converted by celebrated Scottish

missionary Alexander Duff.

Dorothy’s life changed utterly in

1904 when – along with her brothers, Bertie and Neil – she was sent to London

for her schooling. She was just 10 years old.

Dorothy’s parents – both of whom had

spent time in Britain – wanted their children to be, like them, part of the

“England returned” who were increasingly running India on behalf of

the imperial power.

Among the Indian elite, this British

experience had “something of the snob value of a peerage in Great

Britain,” one of the Bonarjee clan remarked.

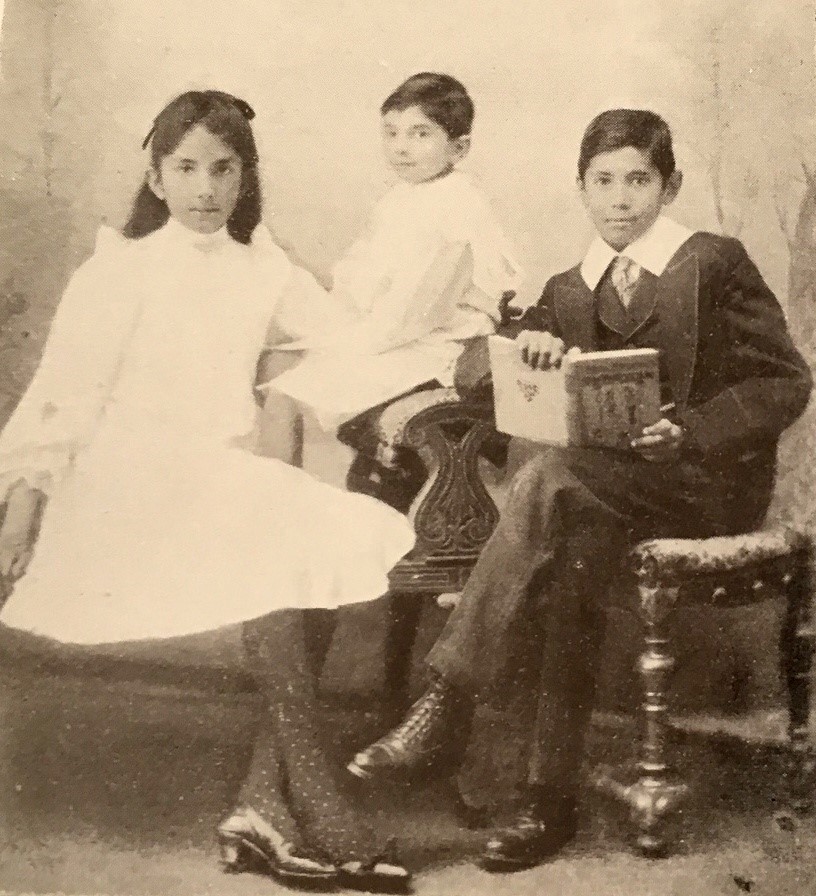

A photograph survives of the three

young Bonarjees at about the time they arrived in London. Dorothy looks demure

in a white dress with a black ribbon in her hair. Bertie, her older brother, is

in a suit and tie. It’s a statement of how English they had become – even

though the world around would always see them as Indian.

Dorothy’s father was a barrister as

well as a landowner. She was probably closer to her mother, who was a strong

advocate of girls’ education. Both daughter and mother were active supporters

in Britain of votes for women. And thanks to her mother, Dorothy had a

privilege rare in either Britain or India a century ago – she was going to get

an education just as good as her brothers.

“At the time of the First World

War, there were about a thousand Indian students at British universities,”

says Dr Sumita Mukherjee at the University of Bristol, who has written a book

about “England returned” Indians. “Around 50 to 70 of these

would have been women.”

In 1912, Dorothy Bonarjee joined

this select group. The family had expected Dorothy to go to the University of

London. But according to family folklore, she found London too

“snobbish” and so opted instead for the University College of Wales

in the largely Welsh-speaking seaside town of Aberystwyth.

“Where the hell is that?!”

her father is said to have exclaimed. But Dorothy got her way. And her brother

Bertie also enrolled there – in part to serve as his sister’s chaperone.

Dorothy’s decision may well have

been shaped by the progressive reputation of the college. “A major

foundational principle for the establishment of the University College at

Aberystwyth was that all religious persuasions and cultural backgrounds were

welcome,” says Dr Susan Davies, an archivist and historian at what is now

Aberystwyth University.

And the college, the oldest of three

forming the University of Wales, also had an impressive record in gender

equality. By the time Dorothy arrived there, approaching half the students were

women, a much higher proportion than at most British universities at this time.

By the time of her graduation ceremony in 1916 – when many of the men were

fighting in Flanders and France – women were in a clear majority.

Dorothy was clearly a popular

student, taking a prominent role in the literary and debating society and

helping edit the college journal. Her big moment came in February 1914 at the

college’s annual Eisteddfod, a pageant and celebration of Welsh culture in

which writers and musicians competed for prizes. While this was not as

prestigious as the national Eisteddfod, it was a major cultural event in the

country’s Welsh-speaking heartlands.

Entrants for the main competition,

poetry in the traditional Welsh style, had a chance to win an imposing

hand-carved oak chair. All poems were submitted under pseudonyms. A Welsh

newspaper, the Cambria Daily Leader, reported on its front page under the

headline Hindu Lady Chaired the “remarkable” scenes when the winner

was announced:

The highest place was awarded to

‘Shita’, for an ode written in English, and described as an excellent and

highly dramatic treatment of the subject… Miss Bonarjee received a deafening

ovation when she stood up and revealed herself as ‘Shita’. She was led up to

the throne… The ‘chairing’ ceremony then proceeded amidst great enthusiasm.

Dorothy’s parents were present to

see their 19-year-old daughter’s success. Her father was prevailed upon to

address the crowd, thanking them for the way they had “received a

successful competitor of a different race and country”. If India had given

birth to a poet, he declared, Wales had educated her and given her an

opportunity to develop her poetic instincts.

Dorothy Bonarjee was the first foreign

student and the first woman to triumph at the college Eisteddfod. This was a

landmark achievement – the first woman to win the chair at the national

Eisteddfod came as recently as 2001.

Emboldened by her success, she

contributed poems to journals including The Welsh Outlook, a monthly magazine

reflecting and encouraging Welsh cultural nationalism. Even after she left

Wales, she continued to publish there.

“She loved the Welsh,”

says her niece Sheela Bonarjee. “She couldn’t speak Welsh – so she was always

an outsider in that sense. But they did accept her.”

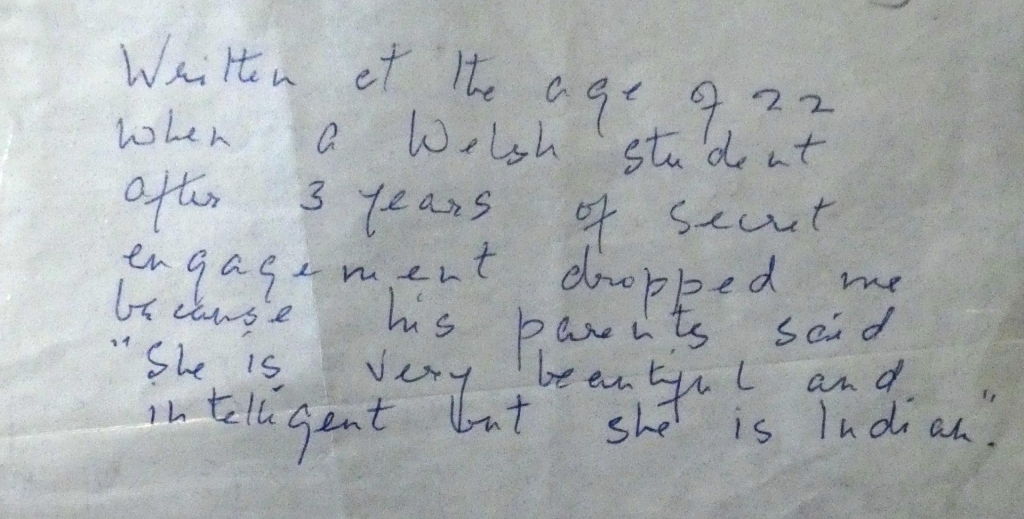

However, Dorothy endured heartbreak

at Aberystwyth as well as acclaim. Sheela Bonarjee still has the battered black

exercise book in which her aunt collated her verse. Alongside one of the poems,

Dorothy jotted down a note: “Written at the age of 22 when a Welsh student

after 3 years of secret engagement dropped me because his parents said ‘She is

very beautiful and intelligent but she is Indian.'”

“It destroyed her. She was

distraught,” Sheela says, recalling the confidences her aunt shared about

that failed romance. “There’s a poem of hers that shows the loss of that

boyfriend.” That poem is called Renunciation:

So I must

give thee up – not with the glow

Of those who

losing much yet rather gain.

But losing

all. Did never martyr go

Along the

bleeding road of useless pain?

Did never

one held prisoner by a creed,

Obsessed by

stern heroic ghosts, made dumb

By those who

answered duty to his need,

With

faithless loathing feet to his fate come?

Dorothy had got used to being the

outsider but there could be a painful price to pay for being different.

Her younger brother, Neil, later

studied at Oxford – and came across a wall of prejudice there. “Indians in

general, it must be said, along with other coloured races were not popular in

the University,” he wrote. His English fellow students “had something

which I had not, namely an Empire. They possessed, while I only belonged.”

Dorothy was undaunted. From

Aberystwyth, she and Bertie returned to London where both took a second degree

course. Again, she was a trailblazer – the first woman student at University

College London to be awarded a law degree. The family then expected the

youngsters to return and make their lives and careers in India. Her brothers

dutifully got on the boat. Dorothy rebelled.

She was caught between different

cultures and social values. She was free-spirited and committed to women’s

equality – not someone who would easily consent to a marriage arranged by her

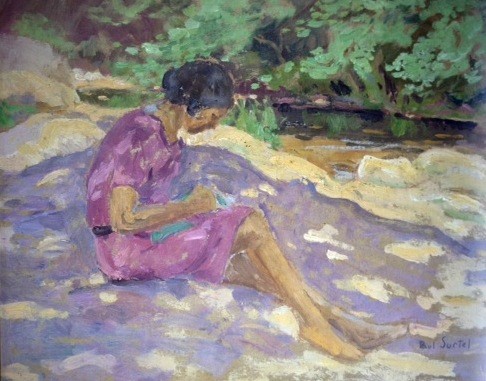

family in India. So she eloped with a French artist, Paul Surtel.

Her father was furious; her mother

seems to have been more understanding. The couple married in 1921, and settled

in the south of France. While Surtel gained distinction as a painter, his wife

largely retreated from public view. They had two children, one of whom died in

infancy, but by the mid-1930s the marriage was over. “Nothing is more

wearing morally,” Dorothy commented, “than a weak husband.”

Her family pleaded with her to

return to India. Once again she refused – a decision she seems later to have

regretted. Her father eventually bought her a small vineyard at Gonferon in

Provence to serve as both home and livelihood. Money was tight. This was not

the life of ease she might have hoped for. She never remarried.

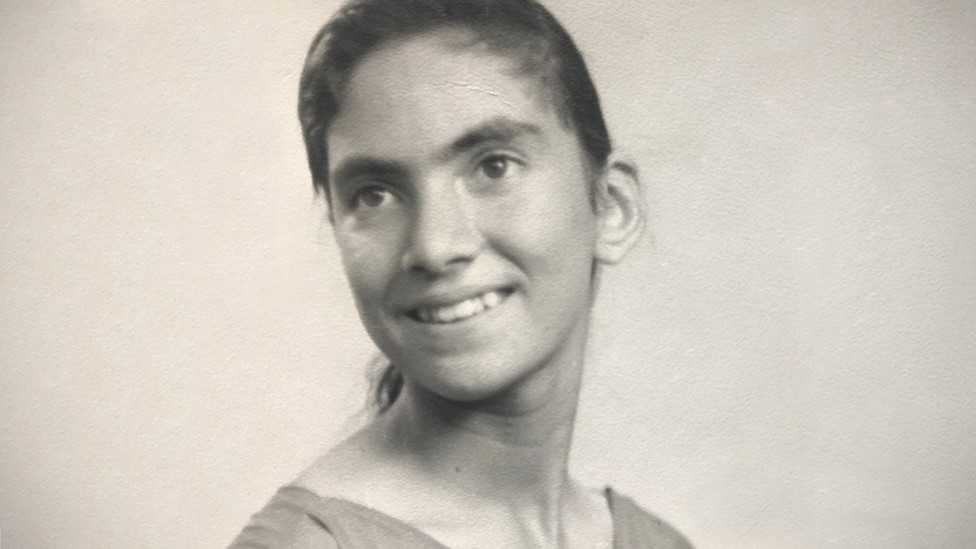

Sheela Bonarjee followed in her

aunt’s footsteps from India to London in the 1950s, and made several visits to

the south of France. She remembers her “Auntie Dorf” as elegant,

confident and unconventional. In some ways she was very French, Sheela recalls.

“She had wine with every meal, which for me as an Indian was very strange

and at times I wondered why I was so sleepy all day.” But she spoke French

with a pronounced accent.

Dorothy Bonarjee kept in touch with

her Welsh friends all her life. In her old age, she paid a pilgrimage to her

old university. “I went with her to Aberystwyth – that must have been in

her 80s,” Sheela Bonarjee recalls of a trip more than 40 years ago.

“It was an important visit for her – to have her memories.”

She now has the distinction of a place in the Dictionary of

Welsh Biography,

the only person of Indian origin among almost 5,000 entries. It’s written by Dr

Beth Jenkins of the University of Essex. “Dorothy certainly embraced Welsh

national culture,” she argues, “and contributed significantly to it

during her time in Aberystwyth.”

Dorothy lived to almost 90. But she

never set foot in India again after leaving as a young girl. The Indian side of

her remained important, though. On high days and holidays she would delight her

French neighbours by dressing up in a sari. But she was in many ways more

French, more English, perhaps even more Welsh, than she was Indian. And

everywhere, she was always the outsider.

When a health emergency prompted

Nathan Romburgh and his sisters to look into their family history, decades

after the end of apartheid, they uncovered a closely guarded secret that made

them question their own identity.